Currently, several methane-fueled rockets are racing into orbit. With Starship from SpaceX, Vulcan from United Launch Alliance (ULA) and Neutron from Rocket Lab, all of America’s most active launch providers are committed to using methalox methane and oxygen.

Upcoming launchers like Blue Origin’s New Glenn and Relativity Space’s Terran family are also on the way, while China’s ZhuQue-2 missile from Landspace may be preferred to fly before any of the American vehicles.

The answer to why methane-fueled rockets have never flown before is a question of chemistry and engineering complexity. But as new designs prioritize reuse as well as in situ resource use (ISRU) for missions to Mars, the mixture of methane and oxygen has become the standard for next-generation launch vehicles.

The stability of combustion is a particular problem in comparison with the most common liquid fuel blends: kerolox (kerosene and oxygen) and hydrolux (hydrogen and oxygen). The boiling points of hydrogen and kerosene Rocket Propelant-1 (RP-1) are very different from those of liquid oxygen (LOX). However, the boiling point of methane is very close to its oxidizer.

Raptor 2 generates more than 230 tons of thrust at sea level, up from Raptor 1’s 185 tons pic.twitter.com/o1Rqjwx6Ql

– SpaceX (SpaceX) February 11, 2022

For a hydrogen engine, combustion occurs in a condition where oxygen droplets are surrounded by hydrogen gas molecules during ignition, and the opposite happens for RP-1. For methane, the boiling points are similar, which means that there is no clear state in which both molecules are during evaporation and combustion. This can lead to combustion instability and make it difficult to use methane as a rocket fuel.

While developing the engines that will power these next-generation vehicles has not been without setbacks and challenges, recent advances in rocket propulsion technology have made methane engines possible. New development efforts were driven by new reuse goals and new space destinations, such as Mars.

Methane is the best propellant to use for refueling situations on the Red Planet. Methane rocket fuel production is possible on Mars with the help of the “Sabatier reaction,” which can produce water and methane from hydrogen and carbon dioxide. This will allow ISRU to Mars Natural Resources to enable new missions by not having to bring in all the required fuel from Earth.

Another reason to use methane is cost. Almost all of the next generation launchers that will use methane are pursuing the idea of reuse in some form or form. neutron And the New Glen Both are, at least initially, aiming at partially reusable vehicles, using propellant landing early stages and consumable upper stages. Starship And the Tiran R, on the other hand, was planned for complete reuse with no consumable phases. even in Vulcan It may still have an engine restoration in its future development plans.

The Vulcan Engine Division, which contains a pair of BE-4 methalox engines, re-enters Earth’s atmosphere for recovery and reuse. (credit: Mac Crawford for NSF/L2)

In addition to reusability, manufacturing improvements have also lowered the cost of building and operating launch vehicles. As these factors decrease, the factor that becomes increasingly important is fuel economy. If the missile launch costs $250 million, it doesn’t matter if the fuel is $2 million or four million per launch. But if the total is $25 million per launch, the fuel becomes a much larger percentage of the total launch costs. Methane is the cheapest of the three liquid fuels, outperforming hydrogen and RP-1 by a large margin.

Another factor, when compared to RP-1 engines specifically, is coke. RP-1 does not burn as cleanly as hydrogen or methane, but leaves behind other substances, comparable to gas in a car. This residue can be stuck in the engine and nozzle and covered over a variety of uses. This effect is visible when in use Falcon 9 stages, in which the missile soars through its exhaust during re-entry and descent, leaving combustion residue on the outside of the missile.

Before the era of reuse, kerolox engines were only used once, so coking was not an issue as new engines were designed for each ride. Coke is not a show stopper for reuse; After all, SpaceX’s kerosene-fuelled Falcon 9 continues to break records for reuse. But as the designs add rapid and complete reusability, reducing coke will reduce the time and effort required to prepare recovered compounds for re-fly.

While hydrogen is a cleaner fuel for combustion, it has its own reuse issues, especially density. Hydrolox is the least energy-dense fuel of the three, which means that the reusable hydrolox phase must be much larger than that fueled by kerolox or methalox. Here another advantage of Metallux emerges: it’s a clean, dense, and efficient propellant. Not only does methane provide a density similar to kerosene, but it also provides a specific boost (efficiency) akin to that of hydrogen rocket engines.

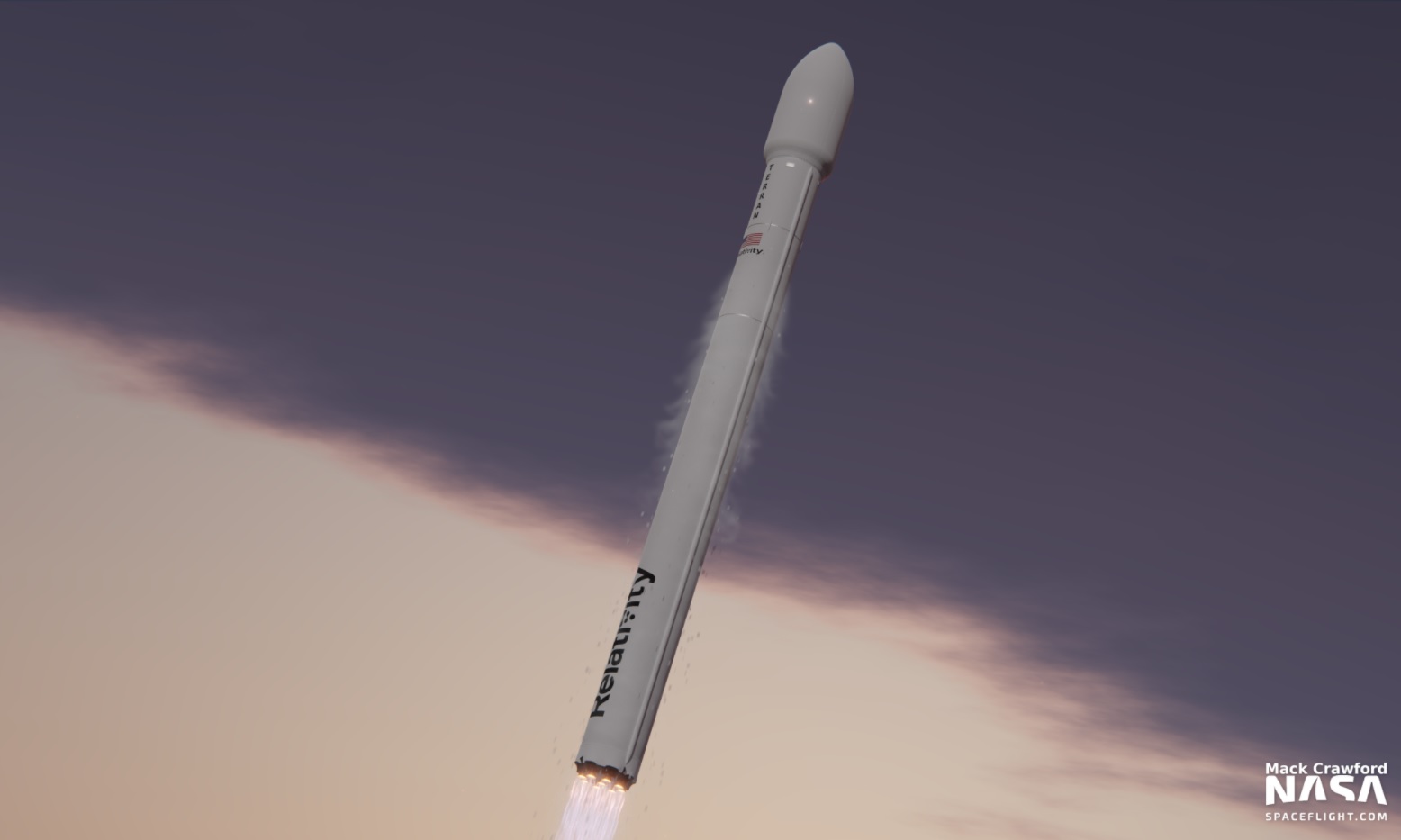

Nine Aeon 1 methalox engines power Terran 1 from Relativity Space, which launched early 2022. (Credit: Mack Crawford for NSF/L2)

Since the temperature of liquid oxygen and liquid methane is very similar, the application of the combined baffle between the two tanks within the phase also becomes easier. With hydrogen, LOX, and very different boiling temperatures, the common tank area can cause thermal problems. With methane, this is not the case, which means that the combined barrier design is a feasible way to reduce vehicle mass.

These new methalox launch vehicles are set to make their first orbital debut this year. While some of them have a significant amount of development work remaining, others are already close to being ready for flight, although it is not yet clear which will be the first methalox-powered vehicle to reach orbit.

Perhaps most notable is the Starship, built by SpaceX. With 33 methane-fueled Raptor engines, it’s a prime example of the Methalox’s advantages. It’s not only designed to carry payloads to Mars and take advantage of Sabatier’s reaction to bring back humans and cargo, but it’s also designed to fly multiple times without major refurbishment. Currently, the entire Starship system is planned for its first flight attempt in 2022 and is one of the candidates for the first methane-fueled rocket to reach orbit.

Another candidate is Terran 1 from Relativity Space. The smallsat launch vehicle is powered by an Aeon 1 engine, which will inform the design of the larger, reusable Aeon R engine. This larger version will power Relativity’s second missile, Terran R, which will be fully reusable and will not fly before 2024. It is still planned Terran 1 small consumable vehicle launched in 2022.

A neutron re-lights the Archimedes’ Metallox engine for landing. (credit: Mac Crawford for NSF/L2)

The last US contender for the first Methalox orbital rocket is ULA’s Vulcan, powered by the BE-4 engine from Blue Origin: the same engine that will power New Glenn. The spent launch vehicle will use a hydrogen-fueled upper stage, but a methane-fueled first stage will be an important part of the orbital launch system. Vulcan’s maiden voyage is currently still scheduled for this year.

While Blue Origin is also developing a Metholux-powered rocket at New Glenn, that vehicle won’t be ready this year, and Blue Origin should supply ULA with BE-4 engines for the Vulcan before New Glenn.

Meanwhile, Rocket Lab’s neutron rocket will be powered by the methalox Archimedes engine, which this year will begin testing for the first time on Neutron in the middle of the decade.

Pleiades-1B captured this image of the latest launch site at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center on 01-15-2022 at 04:26:24 UTC.

It looks like there may be a stage (or mockup) of LandSpace’s ZQ-2 rocket on the platform. pic.twitter.com/plJctAP72E

– Harry Stranger (@Harry__Stranger) January 17 2022

Outside the United States, there is another contender for the first Mytholux rocket in orbit: the Zhuque-2 rocket from China. Powered by the TQ-12 methalox engine, the gas generator engine is slated to debut this year. Recently, instrumentation has hit the board related to the exit pathfinder, and the ZQ-2 could have a very real chance of being the first methane-based rocket in orbit, racing against the Starship, Vulcan and Terran 1.

(Main image: Ship 20 and Booster 4 stacked at the orbital launch site next to the tank farm that will supply the orbiting spacecraft with methane and oxygen before launch. Credit: Mary (Tweet embed) for NSF)

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”