The plane’s engine groaned and its small frame heaved. Through a thin veil of cloud, the spine of the Southern Alps rises like a darkened saw blade.

“I wonder if my favorite glacier will be there,” says lead climatologist Dr. Andrew Lowry. “We had a really, really hot one this summer. It’s hard to say. We’ll just have to see how they go.”

In the pre-sunrise darkness of a Sunday morning, a small group of six scientists huddled on the asphalt of a small airport in Queenstown, strapping cameras into backpacks as a splash of color spilled over the mountains. For most of the next eight hours, they sat contorted in their chairs, spines spasming, lenses trained on the windows to capture the peaks of the Southern Alps as they emerged from a thicket of clouds. This is the New Zealand Annual Snow Line Survey, an annual charter flight run by the Niwa Climate Research Institute that attempts to capture the condition of the country’s glaciers before winter sets in. prepare for the worst.

As the small plane loops around the peaks, the pilot flicks between different maps on a tablet, and compares notes with the science team through a headset to try to track the exact location of the glaciers through cloud cover.

Outside the far window, the blue-gray expanse of the Brewster Glacier looms to the right. Larger glaciers, such as Fuchs and Franz Josef, shrink but still confront you as huge rivers of ice, curled and cracked by the pressure of the slopes flow, a thick ribbon of shrunken pale blue crepe. However, veins of darker rocks appear across other regions, eroding deeper and deeper into the pale centers of the glaciers. Brewster’s glaciers look like a slice of quartz, rippled with thin ribs of black stones and apricot sediments. The thick snow and ice that might once covered it have receded, replacing the dark sheen of the freshly exposed rock.

“It’s really exciting,” says Professor Andrew Mackintosh, the exhibit’s chief scientist, turning his headrest and shrieking at the roar of the engine. “I could not have imagined seeing such changes in my life – they are so profound.”

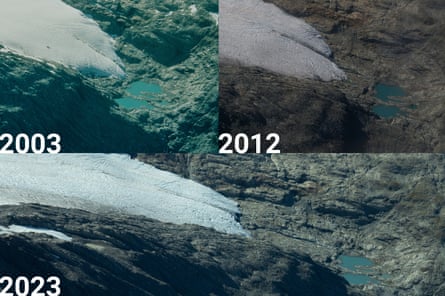

McIntosh, a glaciologist now at Monash University in Australia, helped launch the monitoring program on New Zealand’s Brewster Glacier in 2004. At the time, he was thick and healthy. “It’s been 20 years, and I just wonder how…” “It will take a while for her to be completely lost, but she doesn’t have the characteristics of a happy, living glacier anymore. It looks like something is dissolving and won’t be with us much longer.”

confrontation scene

There is sadness in watching the ice melt. Some of these scientists have been watching these glaciers for decades, and come back every year to take their pictures. They know each of them by name, and they have their own personal favourites. Some of the glaciers they used to record have disappeared over the past decade. Mackintosh and Laurie occasionally leaned back on the gray vinyl chairs to exchange notes, staring out the trembling windows. Someone says, “She looks sloppy.”

“It’s interesting as a scientist, and it’s a little difficult as a human being to see that change,” Mackintosh says. “There is a kind of conflict: the fascination with how a system can change so quickly, combined with the emotional response to seeing the loss of ice that is such an important part of the landscape, so beautiful and so culturally significant.”

“The magnitude of the retreat is facing, even for an ice realm.”

During the winter, snow should cover the glaciers and slopes with a thick, smooth slab of marzipan. This snow nourishes and protects the glacier, adding to the volume of ice before the warmer months clear it away. Typically, ice builds up on its summit and slowly melts from the lower reaches, creating alpine lakes and tar lakes, and feeding the braided rivers below. But the extent of warming changes that dynamic even at high altitudes, causing shrinking ice on glaciers like Brewster’s even at higher elevations. “This is a glacier that is melting everywhere—top, bottom, sides, just bringing everything in,” Mackintosh says.

As the monsoon climate warms through the spring and through the summer, this snow line peels off. As the plane circles the back of Bryant Mountain, Lowry points out where the snowflakes have pulled away from the ice. “Do you see this ice here? All the bluish ice is completely empty, it’s been stripped. … So this entire glacier, about 80%, 90% of it is melting. Any time you see blue ice, it’s naked,” he says.

He shakes his head slightly. “This is lean.”

aWhen the plane lands at the Lake Tekapo airport, Lowry points out the folds and drainage channels of the plains. “18,000 years ago, this whole valley was filled with ice,” he says. But if the movement of ice has been measured over hundreds or thousands of years, it is now moving much faster, setting back warming over the course of years or decades. 2022 was New Zealand’s hottest year – the second consecutive year the record has been broken.

The expedition attempts to document ice lines on more than 50 glaciers, some of which have been monitored as such over the past 46 years. But over time, some standard glaciers replaced as they disappeared, replaced by their higher-altitude cousins. Now, even some of these replacement options appear weak, and Niwa predicts that many important New Zealand glaciers will be gone within this decade.

There is still hope that the glaciers will survive, Lowry says. Some degrees of warming is the difference between New Zealand’s glaciers clinging on or disappearing altogether.

“Quick change is required, and quick action is required to change the course we’re on,” Lowry says. Damage can happen quickly, but the repair is much longer. “This is very sudden and fast [losses] It could happen in a few shockingly warm years,” he says, “but it’s a very slow process of replenishing and rebuilding that ice to its full glory.” “

“We know why glaciers are being lost,” Lowry says. We know that there is a close relationship between temperature change and the changes we see in our glaciers. … We know that this trajectory is largely dictated by carbon dioxide emissions.”

“It’s a little emotional to see such a wonderful, pure part of our natural environment, slip through our fingers. I’d like to share it with my family, friends and especially my daughters, and I don’t know if I’ll ever get that chance… It’s going so fast.

“We need to confront this in a more direct way, in a faster way.”

Wrapped in thick cloud, it’s impossible to see out of plane windows, after all, it was Lowry’s favorite Llawrenny Peaks to document this year.

“In a way I’m kind of happy,” he says. Because I suspect I might have cried if he hadn’t been there.

“Lifelong food lover. Avid beeraholic. Zombie fanatic. Passionate travel practitioner.”