The last time a spacecraft approached Jupiter’s moon Io was more than 20 years ago, it was in the blink of an eye on a typical geological time scale. Most planets in our solar system won’t show much change in a couple of decades.

But Io is different, with volcanic eruptions regularly reshaping parts of the moon’s crust. This means there’s a good chance something has changed on Io since NASA’s Galileo spacecraft last encountered it in 2002.

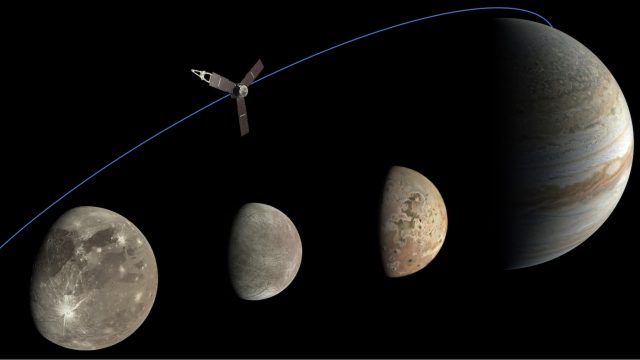

NASA’s robotic Juno spacecraft is delivering new data on Io with a series of flybys, each close to Jupiter’s volcanic moon until a pair of close encounters at a range of less than 1,000 miles (about 1,500 kilometers) in December and February.

The latest flyby on July 30 brought the solar-powered Juno probe about 13,700 miles (22,000 kilometers) from Io’s tortured surface. Juno’s science instruments have been active in the flyby, with the spacecraft’s infrared mapping instrument set to detect heat signatures from volcanic eruptions and pyroclastic flows and an optical imaging camera taking long-range images of Io.

The $1.1 billion Juno mission was launched 12 years ago and reached orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. Its original goal was to study Jupiter’s atmosphere and deep interior. One of his most important scientific findings was the finding of evidence of a potentially large molten core within Jupiter, overturning the hypothesis that Jupiter possesses a smaller solid core at its center.

Juno is now on an extended mission, and scientists have cast a wider net of science observations for the spacecraft’s second semester. The gravitational pull from Jupiter naturally changes Juno’s orbit over time, causing spacecraft to cross the paths of the giant planet’s largest moons. Juno flew by Jupiter’s largest moon, Ganymede, in 2021 and then visited Europe for a flyby in September 2022.

Io, only slightly larger than Earth’s moon, will get a more sustained view from Juno, which began long-range observations of the volcanic moon last year. In May, Juno flew less than 22,000 miles (35,000 km) from Io, followed by a closer flyby on July 30. The spacecraft will see Io again in October before it prepares for what Scott Bolton, Juno’s chief scientist, calls the “high point” of the campaign — the 1,500-kilometer flights scheduled for December 30 and February 3.

Some things never change

While Io is noteworthy for its constant changes, scientists find at least one consistency around Io: a seemingly constantly erupting volcano named Prometheus, also called the “Old Believers of Io.”

NASA’s Voyager spacecraft first discovered the volcano in 1979, and the Galileo probe made numerous observations of Prometheus during its eight-year tour of the Jupiter system from 1995 until 2003. The New Horizons probe heading to Pluto also witnessed the eruption in 2007.

Juno showed the volcano still going, spewing a plume of gas and dust high over Io’s night side.

Fresh from Jupiter, we have new views of its active moon Io, thanks John’s mission. JunoCam even peeked at a volcanic plume! This is Prometheus, the “Old Believer of Io.” More photos: https://t.co/1Vm8NwGA6R pic.twitter.com/YpTAf6IJCu

NASA Solar System August 4, 2023

Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system. The gravitational pull from Jupiter and its moons Ganymede and Europa causes Io to stretch, generating tidal forces that generate heat and lead to volcanic eruptions.

For comparison, Io’s solid surface swells by up to 330 feet (100 meters) during each tidal cycle, according to NASA. The most dangerous trips on land – in liquid water – vary by about 60 feet (18 metres).

During Juno’s May flyby of Io, the spacecraft’s camera captured a view of a region of Io called Volund. Changes are afoot here.

“When I compared it to visible-light images taken of the same area during the Galileo and New Horizons flybys (in 1999 and 2007), I was excited to see changes at Volund, as the lava flow field extended to the west and at another volcano,” said Jason Perry of the Volund Operations Center. HiRISE of the University of Arizona in Tucson: “There have been new lava flows surrounding it north of Volund.” “Io is known for its intense volcanic activity, but after 16 years, it’s very nice to see these changes up close again.”

Scientists have proposed sending a dedicated spacecraft to systematically study Io, similar to how NASA’s Europa Clipper mission will launch next year that will provide a closer look at the icy moon believed to be one of the most promising locations in the solar system for potential life-finding.

But NASA did not approve of the Io mission. This means that Juno observations in the coming months will likely yield only close views of Io for at least the next decade.

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”