Giulia Guidetti

Nature is the ultimate nano maker. The latest evidence of this is an unusual piece of ancient Roman glass (dubbed ‘dazzling glass’) which has a thin, gold-coloured coating. Roman glass shards are characterized by their iridescent colors of blue, green and orange, and are the result of the corrosion process that slowly restructures the glass to form… Photonic crystalsThe shimmering, mirror-like gold sheen of this shell is a rare example with unusual optical properties, according to New paper Published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

It is another example of naturally occurring structural coloration. As mentioned earlier, the bright iridescent colors in butterfly wings, soap bubbles, opals, or beetle shells do not come from any pigment molecules but from how they are structured, which occurs naturally Photonic crystals. In nature, for example, chitin shells (a common polysaccharide in insects) are arranged like roof tiles. Basically, they form a Diffraction gratingExcept that photonic crystals only produce certain colors or wavelengths of light, whereas a diffraction grating would produce the entire spectrum, just like a prism.

Also known as photonic band gap materials, photonic crystals are “tunable,” meaning they are precisely arranged to block certain wavelengths of light while allowing others to pass through. Change the structure by changing the size of the tiles, and the crystals become sensitive to a different wavelength. They are used in optical communications as waveguides and switches, as well as in filters, lasers, mirrors, and many hidden anti-reflection devices.

Scientists can make their own colored structural materials in the laboratory, but it can be difficult to scale the process for commercial applications without sacrificing optical accuracy. So creating structural colors like those found in nature is an active area of materials research. For example, earlier this year, scientists from the University of Cambridge developed An innovative new plant layer becomes cooler when exposed to sunlight, making it ideal for cooling future buildings or cars without the need for any external power source. The films created are colourful, but they are structurally colored in the form of nanocrystals, not due to the addition of pigments or pigments.

Last year, MIT scientists modified a 19th-century holographic technique invented by physicist Gabriel Lippmann to develop chameleon-like films that change color when stretched. These films would be ideal for making bandages that change color in response to pressure, allowing medical personnel to know whether they are wrapping a wound too tightly — an important factor when treating conditions such as venous ulcers, pressure ulcers, lymphedema, and scarring. Kids will love wearing the color-changing bandages, making a great gift for pediatricians. The ability to make large sheets of the material opens up applications in clothing and sportswear.

Fiorenzo Ominito and Giulia Guidetti

Fiorenzo Ominito, a materials scientist at Tufts University who co-authored the new paper, discovered the unique fragment while visiting the Italian Institute of Technology’s Cultural Heritage Technology Center and decided it was worthy of further scientific study. “This beautiful piece of glass sparkling on the shelf caught our attention.” Umineto said. “It was a piece of Roman glass found near the ancient city of Aquileia, Italy.” The center’s director called it “dazzling glass.”

Aquileia was founded by the Romans in 181 BC, initially as a military outpost, but it soon flourished as a center for trade, including forged metals, Baltic amber, wine and ancient glass. “The discovery of a wooden barrel containing 11,000 pieces of glass in a Roman shipwreck in the seawater off Aquileia demonstrates the city’s leading position in the exchange and processing of recycled glass along trade routes,” the authors wrote. By the 2nd century AD, at its peak, the city had a population of 100,000. Its fortunes declined after it was sacked by Attila and the Huns in 452, and again by the Lombards in 590. Today the city has a population of only about 3,500, but it remains an important archaeological site.

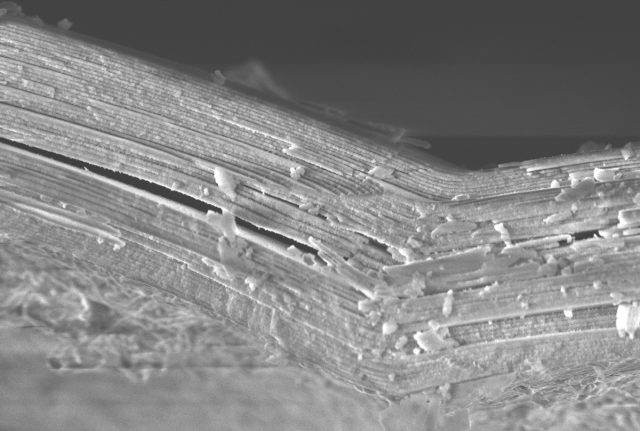

Archaeologists found the “dazzling glass” on the topsoil of an agricultural field during a field survey in 2012 — likely brought to the surface thanks to recent plowing — and were immediately struck by its distinctive multicolored appearance. There were about 780 pieces of glass collected at the same time, but those had the iridescent ivory common in ancient Roman glass. Although this shell was dark green overall, it was covered in a millimeter-thick golden patina that was almost mirror-like in its reflective properties. To learn more, Ominito and his colleagues subjected the shell to both optical microscopy and a new type of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) that reveals not only the material’s nanometer-resolution structure, but also its elemental composition.

Chemical analysis dated the glass to between the first century BC and the first century AD. There was a high level of titanium, indicating that the sand used to make the glass was of Egyptian origin, which usually contains more impurities. As for the dark green color that is still present in most of the piece, the authors indicate that this is due to the presence of iron. Until about the middle of the 2nd century AD, Roman glass was made from either raw Levantine Syrian glass made from relatively pure sand – resulting in a black/purple color – or high-magnesium glass made from impure sand rich in iron and additives. of vegetable ash to give it a dark green color. This is consistent with this new analysis of “dazzling glass.”

Silklab, Tufts University

SEM analysis revealed a precise hierarchical arrangement to form so-called “Bragg stacks” – essentially one-dimensional photonic crystals characterized by alternating layers of high- and low-refractive index materials that give rise to structural color. In an ideal Bragg stack, the layers are the same thickness. But one layer was thicker and denser than the other in the ‘dazzling glass’, giving it that cool metallic look. Specifically, each stack of screws reflected a different narrow wavelength of light, and stacking dozens of them together created a highly reflective gold layer on the shell.

This is evidence that the glass fragment was formed through “a pH-driven chemical change of silica, which does not impose the same stringent physical constraints as found in natural animal systems,” the researchers wrote. According to To Ominito, If they can figure out a way to speed up this process so that it doesn’t take centuries to form such an artifact, “we might find a way to grow optical materials instead of manufacturing them.”

“This is likely a process of erosion and rebuilding.” said co-author Giulia Guidetti, also at Tufts. “The surrounding clay and rain have determined the diffusion of minerals and periodic erosion of silica in the glass. At the same time, 100-nanometer-thick layers combining silica and minerals in cycles have also been collected. The result is an incredibly ordered arrangement of hundreds of layers of crystalline material. Crystals that grow on the surface The glassware is also a reflection of the changes in conditions that occurred on the land as the city developed, a record of its environmental history.

doi: PNAS, 2023. 10.1073/pnas.2311583120 (About digital IDs).

“Beer aficionado. Gamer. Alcohol fanatic. Evil food trailblazer. Avid bacon maven.”